Views - the uncharted mystery

Views are a concept of CUBA that is not that widespread in the web framework world, and to understand it means to prevent running into weird issues around not-loaded data and applications that therefore stop working. Let’s look at the idea behind views and why they are actually pretty neat.

The problem of not loaded data

To get an easy start into the topic, lets take the following example. Imagine, you have a Customer entity that references a CustomerType entity as a N:1 association, meaning that for a customer you can reference a type that describes the customer like “cash cow”, “boor dog” etc. The CustomerType has a name attribute where the actual name is stored.

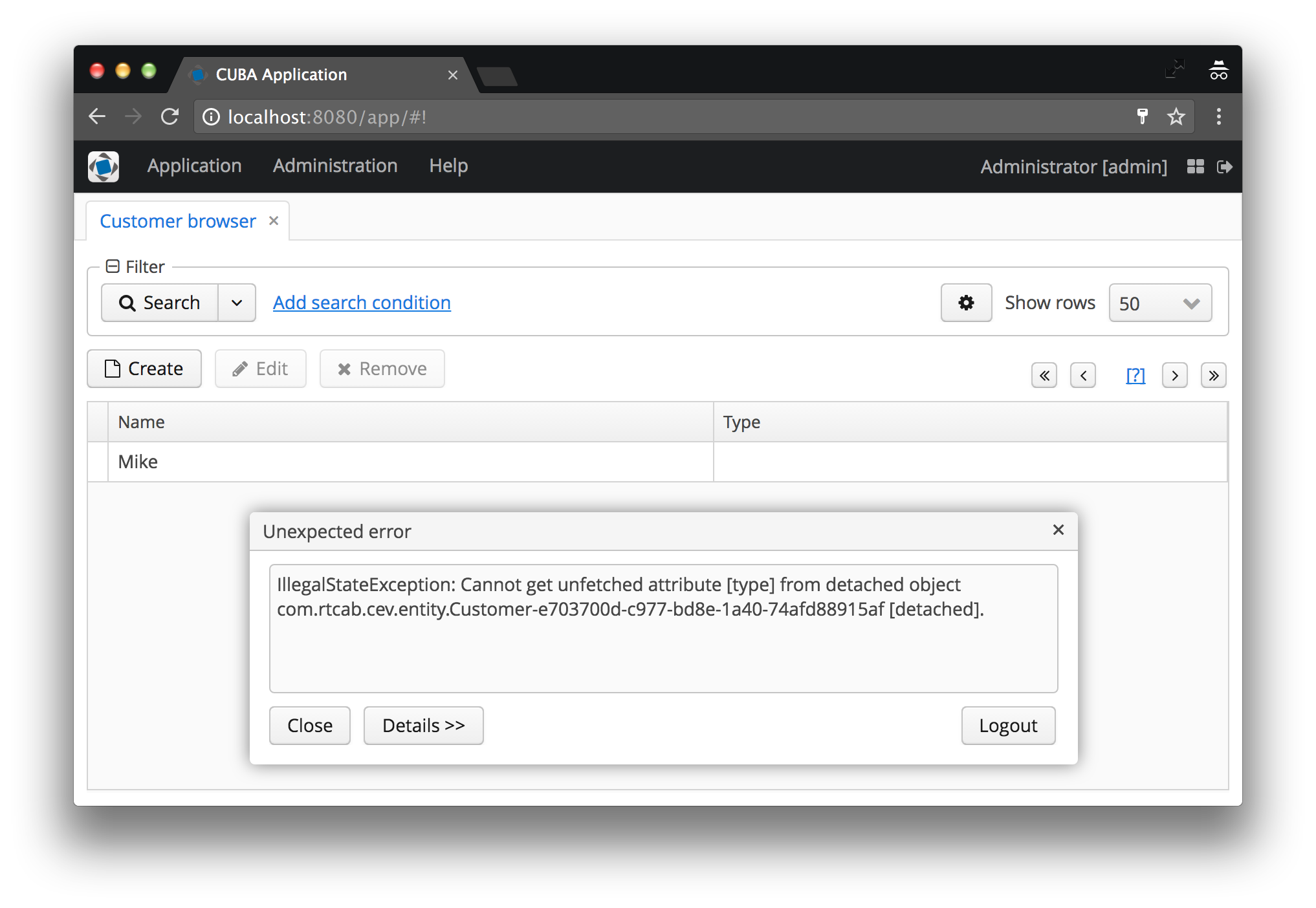

One of issues probably most of CUBA starters (and advanced users) have run into is the following issue:

IllegalStateException: Cannot get unfetched attribute [type] from detached object com.rtcab.cev.entity.Customer-e703700d-c977-bd8e-1a40-74afd88915af [detached].

Have you ever got any kind of this error message? I certainly have in a ton of different situations. In this article we will take a look at the root cause of the problem, why it exists and how to resolve it.

To give you a little introduction about the topic, let’s look at the concept of a view.

What is a view?

A view in CUBA is basically a set of database columns that should be loaded together in one query.

Lets imagine we want to create a UI that has a table of customers where the first column is the name of the customer and the second column is the name of the customerType (like in the picture above). Taking the entity model from above, you end up with two database tables (one for Customer and one for CustomerType). If you do a SELECT * from CEV_CUSTOMER you are only able to get the data within this table (like the name attribute e.g.). To get data from other tables you have to use SQL JOINS in order to get data from multiple tables.

In SQL when using JOIN, the hierachy of the associations is flatted into a list instead of a graph.

In JPQL (what is used by CUBA through JPA), the graph of data can be preserved, so that the java code can easily work with its entity representations and the graph relationship between them.

Nevertheless, the data has to be fetched from the database somehow and transformed into the entity graph. To do that, in the object-relational mapping space (which JPA is) there are two major approaches to query the database.

Lazy loading vs. eager fetching

Lazy loading and eager fetching are two strategies to retrieve the desired data from the database. They distinguish themselves in the question, when the data of referenced tables are loaded. To understand what that means, here’s a little example:

The takeaway of this is, that both options have their own strengths and weaknesses. It is up to you, to decide which one is more accurate in which situation.

N+1 query problem

The N+1 query problem oftentimes occurs when using lazy loading all over the place without actively thinking about it. To illustrate that, let’s have a look at a snippet of Grails code. This does not mean that in Grails everything is lazy loaded (its actually up to you to decide). In Grails, by default your database requests will return instances of the Entity, with all attributes of the table loaded with it. It basically makes a “SELECT * FROM Pet”. When you want to traverse a relationship between entities you do that afterwards. Here’s an example:

function getPetOwnerNamesForPets(String nameOfPet) {

def pets = Pet.findAll(sort:"name") {

name == nameOfPet

}

def ownerNames = []

pets.each {

ownerNames << it.owner.name

}

return ownerNames.join(", ")

}It is a single line of code that will do the traversal here: it.owner.name. Owner is the relationship that has not been loaded in the first request (Pet.findAll). So for each call of this line, GORM will something like “SELECT * FROM Person WHERE id=’…’”. This is called lazy loading. When you count the SQL queries you will end up at N (the person for each invocation of it.owner) + 1 (for the initial Pet.findAll). If you traverse your entity graph further, you will most likely pushing your database to the edge of what is possible.

As a application developer you probably don’t really notice this, because you might think that you will only traverse the object graph.

This implicity with a single line of code hitting the database really hard is what makes lazy loading somewhat dangerous.

Eliminating N+1 queries through CUBA views

In CUBA the N+1 query problem most likely never occurs, because the framework decided to not implicitly do lazy loading. Instead, CUBA has the notion of “views”. Views are basically a definition of what attributes have to be fetched and will be loaded in the entity instances. This would be something like: SELECT pet.name, person.name FROM Pet pet JOIN Person person ON pet.owner == person.id

A view on the one hand represents the column that gets fetched from the own table (Pet) (instead of everything via *), on the other hand represents the columns that have to be loaded via a JOIN.

You can think of a CUBA view as a SQL view for the OR-Mapper since it acts pretty much in the same way.

In CUBA you cannot make an SQL call through the DataManager without using a view. Let’s look at the example from the docs for this:

@Inject

private DataManager dataManager;

private Book loadBookById(UUID bookId) {

LoadContext<Book> loadContext = LoadContext.create(Book.class)

.setId(bookId).setView("book.edit");

return dataManager.load(loadContext);

}In this case we want to load a book via its id. The method setView("book.edit") in the Load context creation defines what view to use when fetching the database. In case you don’t define the view, the data manager will use one of the two standard views that exists for every entity: the _local view. Local means that every attribute that is not a reference to another table will be loaded, nothing else.

Solving the IllegalStateException with views

To get back to our example from above with the knowledge about views, let’s take a look how to resolve the issue.

The error message IllegalStateException: Cannot get unfetched attribute [] from detached object just means, that there is an attribute that you want to display which is not part of the view that you are using for this entity. When we look at the browse screen i used the _local view - which is exactly the problem:

<dsContext>

<groupDatasource id="customersDs"

class="com.rtcab.cev.entity.Customer"

view="_local">

<query>

<![CDATA[select e from cev$Customer e]]>

</query>

</groupDatasource>

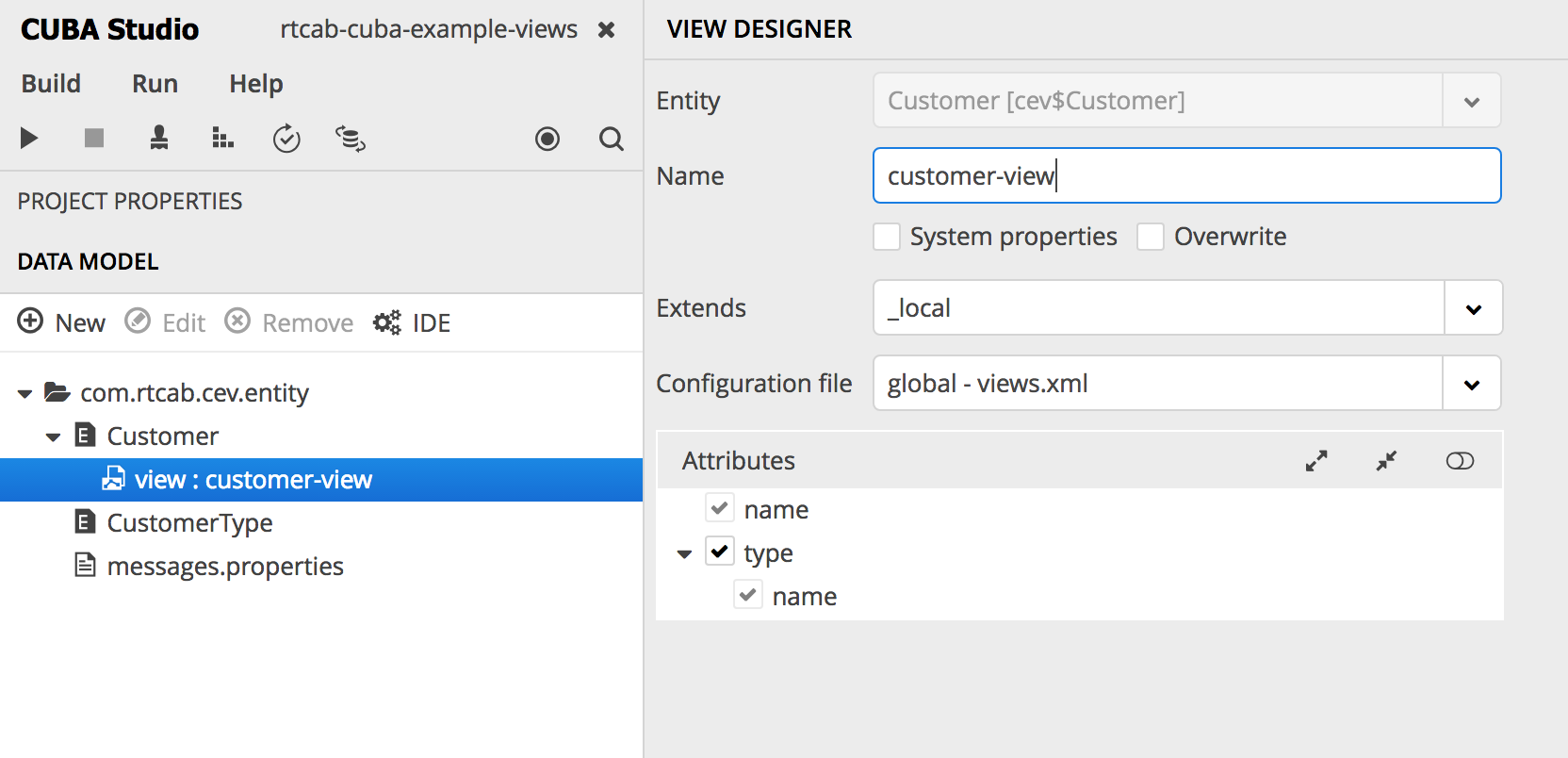

</dsContext>To get rid of the error message, the first thing we need to do is to include our customer type into our view. Since we cannot change the _local view, we can create our own. You can either do it via Studio like this (right click on the entity > create view):

or directly in the views.xml of the application:

<view class="com.rtcab.cev.entity.Customer"

extends="_local"

name="customer-view">

<property name="type"

view="_minimal"/>

</view>After that, you can change the view reference in the browse screen like this:

<groupDatasource id="customersDs"

class="com.rtcab.cev.entity.Customer"

view="customer-view">

<query>

<![CDATA[select e from cev$Customer e]]>

</query>

</groupDatasource>This resolved the issue and referenced data is loaded in the browse screen as well.

The _minimal views and the instance name

The next thing that is relevant when talking about views is the _minimal view. For the local view there is a straightforward definition: all attributes of an entity that are direct attributes of the table.

For the minimal view it is not so obvious, but actually straightforward as well.

In CUBA there is a term called “instance name”. The instance name is pretty much the same as the toString method in a plain old Java program. It is the representation of an entity on the UI and for referencing it. The instance name is defined through the usage of the NamePattern Annotation.

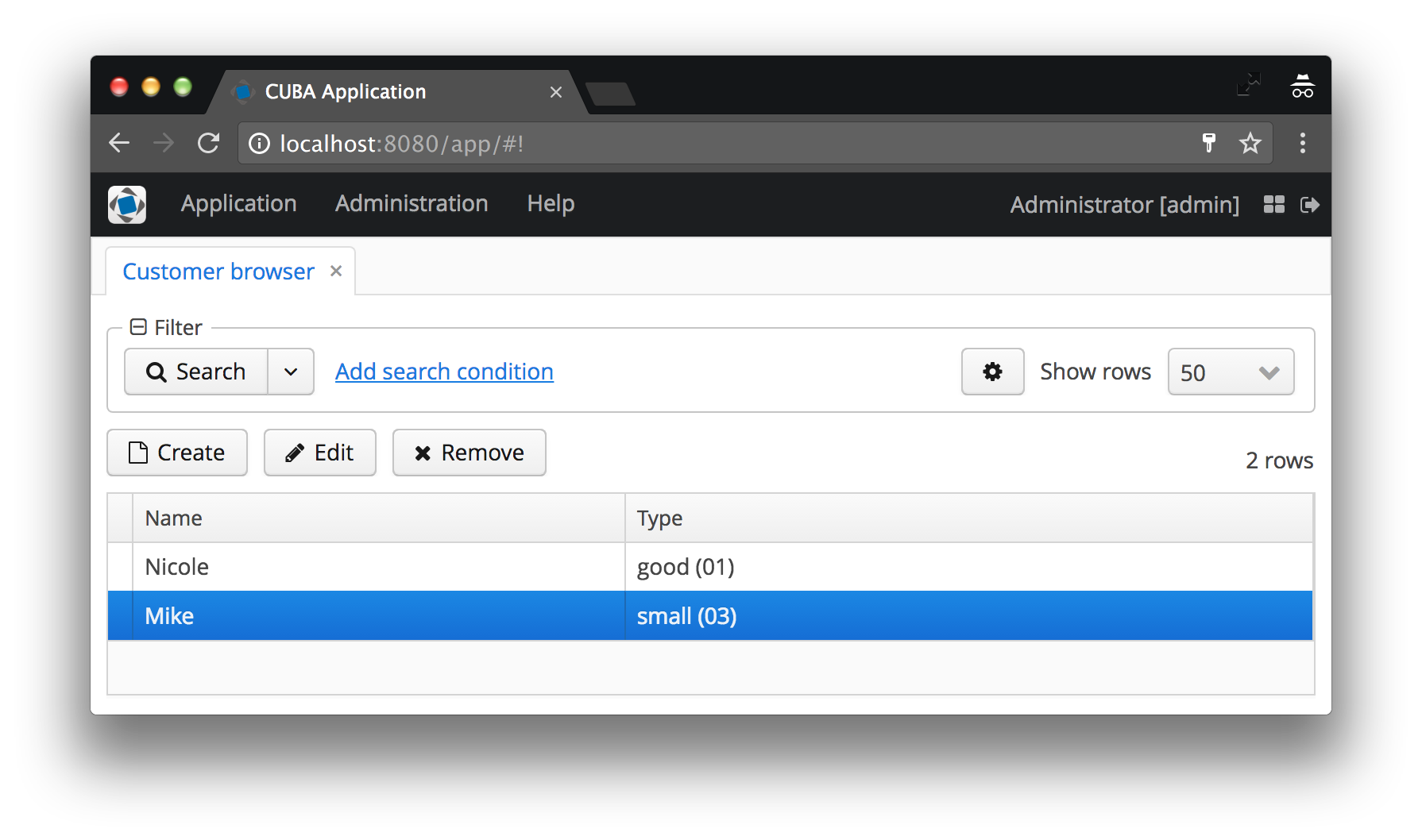

It is used like this: @NamePattern("%s (%s)|name,code"). This will lead to two distinct things:

The instance name defines the UI representation

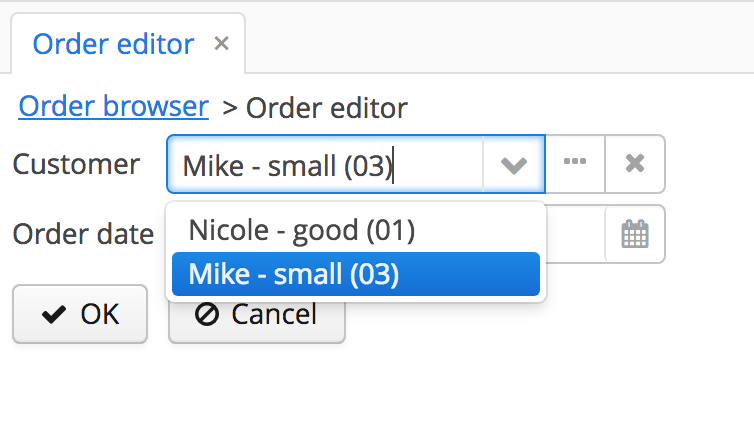

First and foremost it will determine what things in which order will be displayed if the entity is referenced by another entity (e.g. the CustomerType by the Customer) and displayed on the UI.

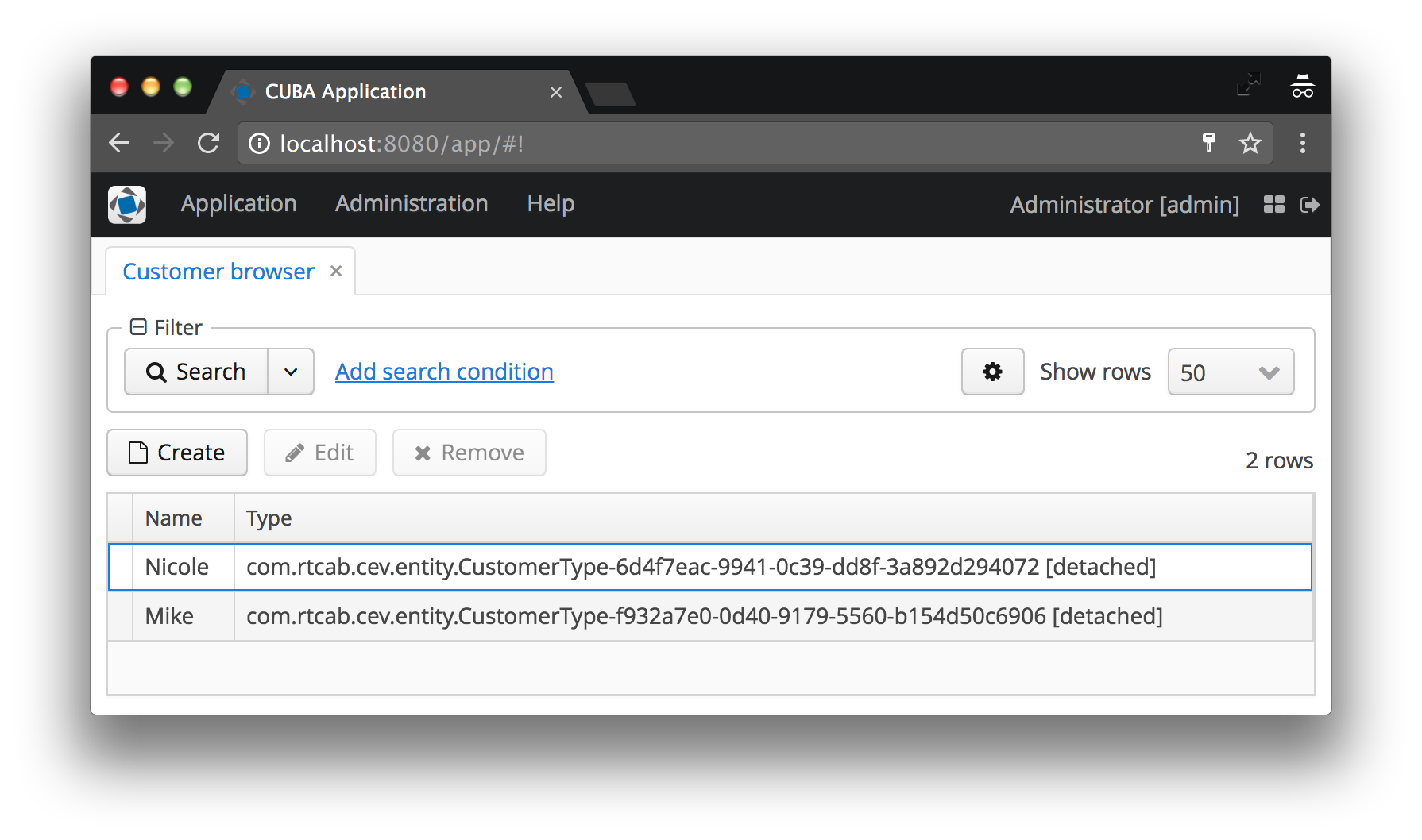

In this case, the Customer Type should be represented as the name of the CustomerType instance followed by the code in brackets. If no instance name is shown, it will display the entity class name as well as the ID, which is mostly not what anyone wants to look at in the UI. See the before / after image for an example:

The instance name defines the attributes of the minimal view

The second thing that gets defined through the Annotation is that every attribute that is mentioned after the Pipe in the annotation value is the minimal view. This seems somewhat obvious because somehow the data has to be displayed in the UI and therefore has to be loaded through the database. But at least for me, I oftentimes don’t really thing about that fact.

Another thing that is very important is that the “minimal” view, compared to “local”, can contain references to other entities. In the example from above i defined the instance name of the Customer entity by using one local attribute of the Customer (name) and one attribute that is a reference (type): @NamePattern("%s - %s|name,type")

Summary

To summarize this topic, let’s recap what is important. What get’s loaded from the database is very explicit in CUBA. It uses view that defines what gets loaded in an eager fashion compared to lazy loading what a lot of other frameworks do.

Views are a little bit cumbersome, but they mostly turn out well in the long run.

I hope, I could clarify your thoughts on what views actually are. There are are some advanced usages as well as gotchas and pitfalls with views in general and the minimal view in particular, that I will shift to the next blog post.